|

A Glint in the Milkman's Eye It all started in early March, right before Easter. Almost on a whim, we decided to go to Peru. We found cheap tickets on a red-eye with an unknown airline, and then -- on another whim -- we checked into whether Continental would let us cash in some frequent flier miles to get Bob and Farrell to join us. They would (only a day later), and just like that, we were off.

At the last minute, Mysterious Airline moved our flight time up by six hours -- creating havoc and stress and hotel reservations. Ironically, after we arrived at the airport, the flight ended up being delayed by the same amount. We left at the original departure time, which brought us to Lima at 5 a.m. after a moderately turbulent flight. Nonetheless, the hotel taxi driver was still waiting there to collect us, looking as weary as I'm sure we did. We had just a few hours before our connecting flight to Puno, so we took a quick spin around the city before crashing at the hotel for a few minutes' nap. A city of 9 million, Lima felt a lot like Mexico City. Dirty, full of traffic and pollution -- and yet at the same time colorful and alive with parks and colonial buildings aplenty. The city felt even more foreign to us than Mexico, but it was amazing how 9 million felt like a small city now!

|

|

Around Lake Titicaca: Even the Locals Laugh at the Name

Promptly at 1 p.m., our flight took off toward Juliaca -- our first destination, near Lake Titicaca. But first we flew toward Cuzco, the old capital of the Inca empire, a city we would visit later in our trip. Quickly, the terrain below turned mountainous and rugged. The landing in Cuzco was about as exciting as landing in Mexico City. It's always something to land in a deep valley -- the pilot suddenly banking sharply, then plunging into a nosedive aimed at the runway. But the city was gorgeous -- lush and green. We took off again and within 45 minutes landed in Juliaca, a small town just north of Lake Titicaca. With a population of about 175,000 and at an elevation of 3822 meters (and the world's tiniest commercial airport), Juliaca greeted us with traditional timeless Peruvian music and excitement. Short of breath and travel weary, we stumbled out of the tiny airport to find the bluest skies and found a collectivo, or minivan offering to take us to Puno, right on the shores of Lake Titicaca. So we hopped in, as did an amazing number of other people (it seemed seats were materialized out of thin air) and we were off. Juliaca felt incredibly foreign as we passed through. The streets were all dirt, and there was dust everywhere. Buildings were made of concrete and adobe (less ornate than you'd find in Santa Fe). There were soft drink billboards absolutely everywhere, and Peruvians of all ages bustling around trying to sell all sorts of everything to everyone. Tricycle taxis outnumbered cars. Imagine the wild west crossed with your image of a town in the developing world, and you've got it.

Driving around Lake Titicaca is surreal. It is incredibly flat, with big hills visible far off in the distance in all directions. The landscape is green, but far from lush. Perhaps even barren. Herds of sheep, llama, and alpaca appear out of nowhere as you speed by. You have to remind yourself that you are on top of the world. And then we caught our first glimpse of Lake Titicaca (a little blurry, as it was taken from inside a speeding vehicle):

Lake Titicaca is the highest lake of its size. At 3820 meters, the lake is more than 170 kilometers long and 60 kilometers wide. That's huge -- not quite as big as Texas, but still fairly respectable. And it just has a neat feeling. People have lived here for so long, but still with only a few exceptions you hardly notice human presence.

Puno is one of these exceptions. With a population of just over 100,000, we wouldn't call it a pretty city. Crazy and bustling, that's about the best you can say for it. People have built here as they've needed, and with what they could find and/or afford. Narrow streets are filled with traffic, and you'd better be careful to look both ways before crossing any street, because the silent tricycle taxis do not stop. There is a main pedestrian street filled with restaurants and people trying to sell all sorts of things -- aggressively. On this street, Stephen dined on a local specialty -- cuy, or roast guinea pig. ("Tastes kinda like squirrel," he'd tell you, "and it's more skin than meat.") The presentation was sensational: spread-eagled on the plate, eyes and teeth and whiskers intact.

We spent an afternoon exploring ancient (Incan and pre-Incan) burial towers outside of Puno. We hiked around Sillustani and Cutimbo. It was our first exposure to the perfectly smoothed and fitted rock style of construction. Families were buried in these towers, with tools and food they'd need in their afterlife. They were often enormous (one is 12 meters tall); somehow, they managed to stand out against the landscape and still blend in with it.

The trip proved fantastic not only for the ruins, but for the scenery and driving adventure. The roads are worse than in Mexico, with potholes everywhere. And I'm not talking about dinky potholes like we complain about in the US, but bomb craters. The taxi driver was all over (and off of) the road to avoid them, at rather high speeds. Bum-py! But things got really exciting when a good 45 kilometers out of Puno (45 kilometers filled with nothing) we heard a noise: pffft!-hisssssssss. We'd blown a tire. The driver stops, and on this tiny road clinging to the side of the mountain, we manage to change the tire. We hop back in the car, and we're off again. Not five minutes later we hear the noise again: pffft!-hisssssssss. The driver looks back at us, shrugs his shoulders knowingly, and steps on the gas.

So off we go, maybe at 70mph down this crappy road full of potholes, driving in an intricate zigzag pattern that involves going off both sides of this mountain road without slowing -- swerving like mad on the flat tire. Periodically, the car would seem to be suspended mid-air over the cliff's edge; we'd get spectacular views of the valley floor below. But the icon of St. Christopher, pasted on the windshield, worked its magic: we were whisked back onto the road each and every time. We made it to the outskirts of town, where the taxi driver promptly pulled off the road into the first tire repair shop we saw.

So that's the story of how we survived the taxi around Puno. As soon as we got back to our hotel and changed our pants, we found that Kristen's brother Bob and his girlfriend Farrell were waiting for us. And so we were ready to move on to the next phase of our trip.

Pictures from around Lake Titicaca:

On Lake Titicaca: Living in National Geographic magazine

From Puno we joined a boatload of other gringos on a three-day excursion to visit some islands in the lake. The first was Uros, some 50 small floating islands constructed from reed which grows naturally in the lake. People have lived on these islands for more than three centuries (stop and think about that). Originally, people moved on the water to avoid aggressive Incas and other tribes. Now there is the distinct advantage that these people don't have to pay taxes, and that tourists will come and gawk at them.

The islands have a really neat sense -- sort of like a houseboat crossed with a treefort, the kind of thing only a kid would dream up. And yet, people live like that! It was surreal. The Uros people survive on fishing and tourism today. They are constantly adding reed layers to their islands. Some are fancier than others (the most impressive was island with a pond in the middle), while others are very basic (just four or five huts). Schools, meeting places, boats for traveling, houses -- everything is made of reeds!

And then on to Amantani. Amantani is a real island. Some 4000 people live there, and it is much less visited than the floating Uros islands. Arriving, you are struck by the unbelievable terracing and colorful clothes worm by both men and women. Our group was split up; each gringo couple was assigned a local family to overnight with. I have never been to a tourist attraction (the island's primary industry is now tourism) where you are so completely integrated into their world rather than just allowed to peek at it from the outside. We climbed one of the two big hills on the island (to an altitude of more than 4100 meters) and watched the sun set. We had dinner with our family, and then were dressed in native clothes and taken off to a party.

Afterwards, we saw an unbelievable southern hemisphere star show (including a constellation that our Australian buddies swore was the "Fish and Chip Basket"). Then we returned to our incredibly modest house with no electricity, and tried to sleep as a thunderstorm hit our tin roof. It was kind of a nice experience -- one that reminded us that many things aren't necessary for happiness.

Other pictures from Uros and Amantani:

I suppose that the island has another notable feature: the courtship rituals. Apparently, when a young man sees an attractive young woman, he pelts her with rocks. If she likes him, she says, "Stop throwing rocks at me!" (If she doesn't like him, she just ignores it... in which case, the young man might persist, hoping that she'll reconsider.) When she asks him to desist, he responds, "But I love you!" She checks him out, and decides on the spot if he's an appropriate mate. If he is, that's it -- they shack up together for the next couple years during a period called the 'proof of love'. And what proof is the world looking for? A child, nothing more, nothing less. If no child is produced (presumably because they can't stand each other enough to do you-know-what together), the trial marriage is dissolved. If they do have children, then the young man has to ask the father's permission over a friendly drink.

The woman's father supposedly always rejects the offer of marriage. The young man buys him another drink, and asks again. Rejection again. Wash, rinse, repeat; once the father-in-law has had his fill of free drinks, he allows the marriage.

Anyhow, back to Taquile. Most of the group spent only a couple of hours on the island, but we had arranged to stay with another family. Since this was uncommon, we had an even more authentic experience here. We were met by a guy in the main village, and were walked one hour to the family's home on the other end of the island. Along the way, various traditional plants were pointed out and discussed through broken Spanish and charades. We saw fresh lima beans growing in the fields (lima, Lima -- see the connection?). We saw honest-to-goodness Texas bluebonnets, which are grown for their beans. And we saw lots and lots and lots of potatoes. Apparently, Peru is where most of the world's potato chips are grown.

When we arrived at our host's house, we saw a couple of middle aged men, one woman, a grandpa, and three kids hanging around the house. We were invited to watch as they wove, and were given more agricultural demonstrations. The traditional agriculture was amazingly well-informed; in order to prevent erosion and to maximize production, the craggy island had been transformed into beautifully terraced plots of garden and small pastures. We played with the kids and introduced them to juggling. Then our host took us on a serious hike (the kind where you have to use your imagination to see the trail). He showed us some 2000 year old carvings; he showed the guys the best swimming spot in the lake (cold, cold, cold!); he told us more tidbits and trivia about the local way of life.

Other pictures from Taquile:

Cuzco and around: the Incan capital

Cuzco was our next destination, a day's journey by choo-choo train across the high plains. It's a city of 350,000 at an elevation of some 3300 meters (ahhhh, I can breathe again!). Cuzco was the heart of the Incan empire -- and there is some story about a guy wandering around for ages and ages looking for a place where he could pierce the earth with his dagger. And apparently Cuzco was it. Now it's tourist central, and the jumping board for treks and trips into the surrounding mountains. We ate lots of good food, saw a Semana Santa procession (from around the corner and way back), got rained on, talked to kids selling more crap stuff, and hung out a lot with Bob and Farrell.

Now the main cathedral, as any good guide will tell you, is a fine example of the blending of indigenous and colonial cultures. There are mirrors all around to show the heathens their reflections -- something they hadn't seen before, a magic sign that the European gods had powers that theirs didn't. (Yup, that sounds like "blending" to me.) It wasn't until I saw this painting that I was convinced of any integration of cultures. It's a native artist's vision of Christ and his disciplines at the Last Supper: eating guinea pig, the food of the kings (and consequently, of the King of Kings?).

Oh, and it's the oldest catholic cathedral in South America. (But not in all of the Americas -- that's in Mexico City, with us.)

After exploring the city, we set off to see some nearby ruins. We visited Sacsayhuaman, a name which is the butt of almost as many jokes as Lake Titicaca. (Say it aloud, keeping in mind that the Spanish hu sounds like a 'w': sec-sey-wa-man.) The site is the ruins of an old fortress or something -- today, however, just a bunch of really big carved rocks. The largest is over 360 tons. The nearest quarry was some fifteen kilometers away, up and down many sizeable hills. And the Inca had no beasts of burden, which leaves only two plausible explanations how they got there: the superhuman Incan god-kings, or aliens.

After we admired the sexy woman, we visited Tambo Machay, another Incan site, this one with a cool fountain. This was a ceremonial stone bath, and still runs from a mountain spring somewhere nearby. Not sure if you can tell, but there are three parts to the fountain; Incas' lucky number was three.)

Cuzco and around:

The Inca Trail to Machu Picchu: Finally!

First, some facts about the Incan trail. We've misplaced our notes, so we're going to have to rely on recollection. If I recall correctly, it was about 1000 kilometers long, which we death-marched in four days. And it's mostly uphill. And did I mention that we had to carry 100-pound sacks of concrete? Yeah. It was grueling. Most gringos die from asphyxiation at the high altitudes, but fortunately we were halfway acclimated from living in Mexico City.

And if all that wasn't bad enough, there was one woman in our group who bitched and whined about it the whole time.

So anyhow. We set off Wednesday morning before the sun was even out. We lugged our belongings to the SAS office, our departure point, where a bus met us. We were whisked off to the Sacred Valley in this amphibious superbus, equipped with bulldozer treads and air conditioning and bulletproof glass and everything else you might need in order to safari in comfort. Except shocks. So everyone was forced to try to sleep in order to ward off motion sickness -- everyone except for Stephen, who sang schoolbus songs in order to let everyone else know that he was bored.

Finally, we made it to the starting point. Or at least somewhere near it. Our machine was too wide for the tiny dirt road (you'd think that they'd think of that when designing a safari supermobile?). But what's a few extra kilometers when you're already walking a thousand? So set off.

The second day was a good bit harder. We were woken up at 6 a.m., and on the trail by 7. The morning was spent hiking up. (And by "up", I really mean nothing but up.) For four solid hours. We reached our maximum altitude of 4200 meters. It was rainy and FREEZING at the top. And so cloudy that there really was no view.

So we ate a few grubs and maggots, caught our breathe, and started the three hour hike straight down. Over wet, loose rocks. Kristen, for those of you who don't know, it's a big fan of downhill trails. Stephen, on the other hand, is sure-footed as a mountain donkey; he fell into briar-filled ditches only twice.Upon arrival to our campsite (all clouded in and still raining), we collapsed in the tent. About an hour later, we heard a couple people outside exclaiming how gorgeous our campsite was. And it truly was. We were camping on a steep ridge in a cloud forest.

The third day wasn't so bad -- mostly. The first hundred kilometers were gorgeous. We hiked through rain forest and to another high pass (which was clouded over) and then to a higher pass (which wasn't). We had a bit of sun, which allowed clothes and things to dry. Our guards even let Bob have a drink of water. At one point, we saw an indigenous house that had been transformed into a store; much rejoicing ensued. We got to explore all sorts of ruins.

And then we hiked down 1,000 meters in one go.

That night was a little bit of a let down. We camped with the masses at a campsite complete with a restaurant, bar and hot showers. (You'd think that we'd be desperate for showers at that point, but we were too sore to bother.) Power lines visible on the neighboring hills. Trains blasting in the distance. We'd trekked into the wilderness for days, only to reach our electric-powered ultra-modern destination. We were bothered by the thought for a few minutes, but then we were too tired to think.

The guards woke us up at four the next morning for our final march to Machu Picchu. Well. To stand in line in dark for a few hours, waiting to have our trail tickets check and whatnot. In the rain. And sleet. With a monsoon blowing. And no discreet places to use as a toilet. After the real hike began, we discovered that all of the ruins and overlooks -- the ones that we got up so early to see? -- were completely clouded over.

The lack of a toilet was becoming a rather serious issue. Then one member of our group stepped over the edge of a cliff in the dark, which only delayed things further. Especially the toilet thing. But yeah, I'll be honest: right then, at the pinnacle of our entire Peruvian excursion, we were hating life.

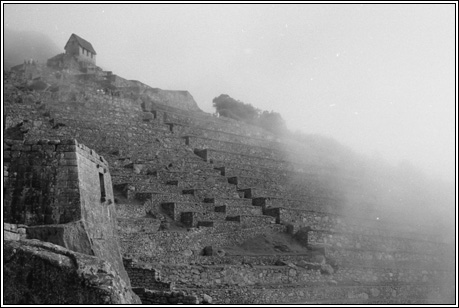

But anyhow, these things get themselves sorted out; a few hours later, Kristen traded her soul to a security guard in order to let us crap in a place that we really shouldn't have been allowed to crap. And soon enough, all of our group had reconvened at Machu Picchu. We make our way along a path to what would have been perhaps a house. Our guide starts to tell us the legends of Machu Picchu: when it was built, when it was rediscovered, what the young maiden to priest ratio was. Then, we noticed something... the fog was breaking a bit. Suddenly we could enormous terraces -- loads of them! And buildings! And mountains beyond that!

So, anyhow, there you have it. It was as glorious as it was supposed to be. No place in the world has the same magical atmosphere -- if you squinted your eyes, you could see the young maidens running around, strings of flowers flowing from their hair, ready to be sacrificed to the priests. You could hear the long-distance messengers, who had just run over our same Inca trail, carrying news from the king in Cuzco. You could smell the guinea pigs, growing fat in preparation for dinnertime.

I guess we could go on and on about this or that, but it all seems corny in retrospect. Instead, we'll just confuse you with a few random photos:

Email Kristen: kristen@plumgreen.com

Email Stephen: stephen@plumgreen.com